Note

-

Download Jupyter notebook:

https://docs.doubleml.org/stable/examples/py_double_ml_plpr.ipynb.

Python: Static Panel Models with Fixed Effects#

In this example, we illustrate how the DoubleML package can be used to estimate treatment effects for static panel models with fixed effects in a partially linear panel regression DoubleMLPLPR model. The model is based on Clarke and Polselli (2025).

[1]:

import optuna

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

from sklearn.base import clone

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.preprocessing import PolynomialFeatures

from sklearn.compose import ColumnTransformer

from sklearn.pipeline import make_pipeline

from sklearn.base import BaseEstimator, TransformerMixin

from sklearn.linear_model import LassoCV

from lightgbm import LGBMRegressor

from doubleml.data import DoubleMLPanelData

from doubleml.plm.datasets import make_plpr_CP2025

from doubleml import DoubleMLPLPR

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings("ignore")

Data#

We will use the implemented data generating process make_plpr_CP2025 to generate data similar to the simulation in Clarke and Polselli (2025). For exposition, we use the simple linear dgp_type="dgp1", with 150 units, 10 time periods per unit, and a true treatment effect of theta=0.5.

We set time_type="int" such that the time variable values will be integers. It’s also possible to use "float" or "datetime" time variables with DoubleMLPLPR.

[2]:

np.random.seed(123)

data = make_plpr_CP2025(num_id=150, num_t=10, dim_x=30, theta=0.5, dgp_type="dgp1", time_type="int")

data.head()

[2]:

| id | time | y | d | x1 | x2 | x3 | x4 | x5 | x6 | ... | x21 | x22 | x23 | x24 | x25 | x26 | x27 | x28 | x29 | x30 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 | -1.290479 | 0.908307 | 1.710715 | -1.853675 | -1.473907 | 1.366514 | -0.322024 | 2.944020 | ... | -1.828362 | -3.010547 | -0.840202 | -3.085159 | 1.169952 | -0.954107 | -3.925198 | -0.779510 | -0.430700 | 1.004298 |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | -2.850646 | -1.316777 | -0.325043 | 4.178599 | -1.159857 | -0.139527 | -0.230115 | -0.631976 | ... | -0.724172 | -0.421045 | -2.012480 | -2.081784 | -2.734123 | -0.879470 | -2.141218 | 4.598401 | -4.222797 | -2.523024 |

| 2 | 1 | 3 | -4.338502 | -1.756120 | -0.897590 | 1.505972 | -0.925189 | 1.511500 | -2.206561 | 0.132579 | ... | 1.766109 | -2.252858 | -2.919826 | -1.974066 | -0.773881 | 0.244633 | -1.727550 | 1.665467 | 0.562291 | -1.553616 |

| 3 | 1 | 4 | -2.713236 | 0.934866 | 1.987849 | 2.596228 | -0.220666 | -0.480717 | -3.966273 | -0.911226 | ... | 0.856124 | 0.727759 | -0.501579 | 1.077504 | 2.268052 | -3.821422 | 1.629055 | -0.220834 | -1.185091 | -5.462884 |

| 4 | 1 | 5 | -5.782997 | -4.357881 | -3.086559 | 3.796975 | -1.539641 | -2.425617 | -1.020599 | -1.666200 | ... | 2.617215 | -1.231835 | -0.891350 | 0.246981 | 2.489642 | 0.319735 | -2.810366 | 0.585826 | 3.643749 | 0.147147 |

5 rows × 34 columns

To create a corresponding DoubleMLPanelData object, we need to set static_panel=True and specify id_col and time_col columns.

[3]:

data_obj = DoubleMLPanelData(data, y_col="y", d_cols="d", t_col="time", id_col="id", static_panel=True)

Model#

The partially linear panel regression (PLPR) model extends the partially linear model to panel data by introducing fixed effects \(\alpha_i^*\).

The PLPR model takes the form

where

\(Y_{it}\) outcome, \(D_{it}\) treatment, \(X_{it}\) covariates, \(\theta_0\) causal treatment effect

\(g_1\) and \(m_1\) nuisance functions

\(\alpha_i^*\), \(\gamma_i\) unobserved individual heterogeneity, correlated with covariates

\(U_{it}\), \(V_{it}\) error terms

Further note \(\mathbb{E}[U_{it} \mid D_{it}, X_{it}, \alpha_i^*] = 0\) and \(\mathbb{E}[V_{it} \mid X_{it}, \gamma_i]=0\), but \(\mathbb{E}[\alpha_i^* \mid D_{it}, X_{it}] \neq 0\).

Alternatively we can write the partialling-out PLPR as

with nuisance function \(\ell_1\) and fixed effect \(\alpha_i\).

Assumptions#

Define \(\xi_i\) as time-invariant heterogeneity terms influencing outcome and treatment and \(L_{t-1}(W_i) = \{ W_{i1}, \dots, W_{it-1} \}\) as lags of a random variable \(W_{it}\) at wave \(t\).

No feedback to predictors

\[X_{it} \perp L_{t-1} (Y_i, D_i) \mid L_{t-1} (X_i), \xi_i\]Static panel

\[Y_{it}, D_{it} \perp L_{t-1} (Y_i, X_i, D_i) \mid X_{it}, \xi_i\]Selection on observables and omitted time-invariant variables

\[Y_{it} (.) \perp D_{it} \mid X_{it}, \xi_i\]Homogeneity and linearity of the treatment effect

\[\mathbb{E} [Y_{it}(d) - Y_{it}(0) \mid X_{it}, \xi_i] = d \theta_0\]Additive Separability

\[\begin{split}\begin{align*} \mathbb{E} [Y_{it}(0) \mid X_{it}, \xi_i] &= g_1(X_{it}) + \alpha^*_i \quad \text{where } \alpha^*_i = \alpha^*(\xi_i), \\ \mathbb{E} [D_{it} \mid X_{it}, \xi_i] &= m_1(X_{it}) + \gamma_i \quad \text{where } \gamma_i = \gamma(\xi_i) \end{align*}\end{split}\]

For more information, see Clarke and Polselli (2025).

To estimate the causal effect, we can create a DoubleMLPLPR object. The model described in Clarke and Polselli (2025) uses block-k-fold cross-fitting, where the entire time series of the sampled unit is allocated to one fold to allow for possible serial correlation within each unit which is common with panel data. Furthermore, cluster robust standard error are employed.

DoubleMLPLPR implements both aspects by using id_col as the cluster variable.

Estimation Approaches#

Clarke and Polselli (2025) describes multiple estimation approaches, which can be set with the approach parameter. Depending on the type of approach, different data transformations are performed along the way.

Transformation Approaches#

The transformation approaches include first differences (fd_exact) and within-group (wg_approx) transformations.

fd_exact#

Consider first differences (FD) transformation (fd_exact) \(Q(Y_{it})= Y_{it} - Y_{it-1}\), under the assumptions from above, Clarke and Polselli (2025) show that \(\mathbb{E}[Y_{it}-Y_{it-1} | X_{it-1},X_{it}] =\Delta \ell_1 (X_{it-1}, X_{it})\) and \(\mathbb{E}[D_{it}-D_{it-1} | X_{it-1},X_{it}] =\Delta m_1 (X_{it-1}, X_{it})\). Therefore, the transformed nuisance function can be learnt as

\(\Delta \ell_1 (X_{it-1}, X_{it})\) from \(\{ Y_{it}-Y_{it-1}, X_{it-1}, X_{it} : t=2, \dots , T \}_{i=1}^N\),

\(\Delta m_1 (X_{it-1}, X_{it})\) from \(\{ D_{it}-D_{it-1}, X_{it-1}, X_{it} : t=2, \dots , T \}_{i=1}^N\).

[9]:

dml_plpr_fd_exact = DoubleMLPLPR(data_obj, ml_l=ml_l, ml_m=ml_m, approach="fd_exact", n_folds=5)

dml_plpr_fd_exact.data_transform.data.head()

[9]:

| id | time | y_diff | d_diff | x1 | x2 | x3 | x4 | x5 | x6 | ... | x21_lag | x22_lag | x23_lag | x24_lag | x25_lag | x26_lag | x27_lag | x28_lag | x29_lag | x30_lag | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | -1.560167 | -2.225084 | -0.325043 | 4.178599 | -1.159857 | -0.139527 | -0.230115 | -0.631976 | ... | -1.828362 | -3.010547 | -0.840202 | -3.085159 | 1.169952 | -0.954107 | -3.925198 | -0.779510 | -0.430700 | 1.004298 |

| 1 | 1 | 3 | -1.487856 | -0.439343 | -0.897590 | 1.505972 | -0.925189 | 1.511500 | -2.206561 | 0.132579 | ... | -0.724172 | -0.421045 | -2.012480 | -2.081784 | -2.734123 | -0.879470 | -2.141218 | 4.598401 | -4.222797 | -2.523024 |

| 2 | 1 | 4 | 1.625266 | 2.690986 | 1.987849 | 2.596228 | -0.220666 | -0.480717 | -3.966273 | -0.911226 | ... | 1.766109 | -2.252858 | -2.919826 | -1.974066 | -0.773881 | 0.244633 | -1.727550 | 1.665467 | 0.562291 | -1.553616 |

| 3 | 1 | 5 | -3.069761 | -5.292747 | -3.086559 | 3.796975 | -1.539641 | -2.425617 | -1.020599 | -1.666200 | ... | 0.856124 | 0.727759 | -0.501579 | 1.077504 | 2.268052 | -3.821422 | 1.629055 | -0.220834 | -1.185091 | -5.462884 |

| 4 | 1 | 6 | -1.094799 | 0.551051 | 0.289315 | -2.823134 | -3.137179 | -1.425923 | -0.730116 | 0.232687 | ... | 2.617215 | -1.231835 | -0.891350 | 0.246981 | 2.489642 | 0.319735 | -2.810366 | 0.585826 | 3.643749 | 0.147147 |

5 rows × 64 columns

We see that the outcome and treatment variables are now labeled y_diff and d_diff to indicate the first-difference transformation. Moreover, lagged covariates \(X_{it-1}\) are added and rows for the first time period are dropped.

[10]:

dml_plpr_fd_exact.fit()

print(dml_plpr_fd_exact.summary)

coef std err t P>|t| 2.5 % 97.5 %

d_diff 0.511822 0.032746 15.630162 4.536510e-55 0.447641 0.576002

wg_approx#

For within-group (WG) transformation (wg_approx) \(Q(X_{it})= X_{it} - \bar{X}_{i}\), where \(\bar{X}_{i} = T^{-1} \sum_{t=1}^T X_{it}\), approximate the model as

Similarly for the partialling-out PLPR

\(\ell_1\) can be learnt from transformed data \(\{ Q(Y_{it}), Q(X_{it}) : t=1,\dots,T \}_{i=1}^N\),

\(m_1\) can be learnt from transformed data \(\{ Q(D_{it}), Q(X_{it}) : t=1,\dots,T \}_{i=1}^N\).

[11]:

dml_plpr_wg_approx = DoubleMLPLPR(data_obj, ml_l=ml_l, ml_m=ml_m, approach="wg_approx", n_folds=5)

dml_plpr_wg_approx.data_transform.data.head()

[11]:

| id | time | y_demean | d_demean | x1_demean | x2_demean | x3_demean | x4_demean | x5_demean | x6_demean | ... | x21_demean | x22_demean | x23_demean | x24_demean | x25_demean | x26_demean | x27_demean | x28_demean | x29_demean | x30_demean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1.543571 | 1.760660 | 2.207607 | -2.039516 | -0.642847 | 1.014204 | 0.384166 | 1.826013 | ... | -3.162933 | -2.475942 | 0.000728 | -3.344219 | 0.082829 | -1.351303 | -2.670511 | -1.275344 | 0.407596 | 2.187878 |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | -0.016596 | -0.464424 | 0.171849 | 3.992759 | -0.328797 | -0.491837 | 0.476074 | -1.749982 | ... | -2.058743 | 0.113560 | -1.171550 | -2.340844 | -3.821246 | -1.276666 | -0.886531 | 4.102567 | -3.384501 | -1.339444 |

| 2 | 1 | 3 | -1.504452 | -0.903767 | -0.400698 | 1.320131 | -0.094129 | 1.159190 | -1.500371 | -0.985427 | ... | 0.431538 | -1.718253 | -2.078895 | -2.233126 | -1.861004 | -0.152563 | -0.472863 | 1.169632 | 1.400587 | -0.370036 |

| 3 | 1 | 4 | 0.120814 | 1.787219 | 2.484741 | 2.410387 | 0.610394 | -0.833027 | -3.260084 | -2.029232 | ... | -0.478447 | 1.262364 | 0.339352 | 0.818443 | 1.180930 | -4.218618 | 2.883741 | -0.716668 | -0.346795 | -4.279304 |

| 4 | 1 | 5 | -2.948947 | -3.505528 | -2.589667 | 3.611134 | -0.708582 | -2.777927 | -0.314410 | -2.784206 | ... | 1.282645 | -0.697230 | -0.050420 | -0.012080 | 1.402519 | -0.077461 | -1.555679 | 0.089991 | 4.482045 | 1.330727 |

5 rows × 34 columns

We see that the outcome, treatment and covariate variables are now labeled y_demean, d_demean, xi_demean to indicate the within-group transformations.

[12]:

dml_plpr_wg_approx.fit()

print(dml_plpr_wg_approx.summary)

coef std err t P>|t| 2.5 % 97.5 %

d_demean 0.495323 0.025841 19.167824 6.872435e-82 0.444675 0.545972

For the simple linear data generating process dgp_type="dgp1", we can see that all approaches lead to estimated close the true effect of theta=0.5.

The data_original property additionally includes the original data before any transformation was applied.

[13]:

dml_plpr_wg_approx.data_original.data.head()

[13]:

| id | time | y | d | x1 | x2 | x3 | x4 | x5 | x6 | ... | x21 | x22 | x23 | x24 | x25 | x26 | x27 | x28 | x29 | x30 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 | -1.290479 | 0.908307 | 1.710715 | -1.853675 | -1.473907 | 1.366514 | -0.322024 | 2.944020 | ... | -1.828362 | -3.010547 | -0.840202 | -3.085159 | 1.169952 | -0.954107 | -3.925198 | -0.779510 | -0.430700 | 1.004298 |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | -2.850646 | -1.316777 | -0.325043 | 4.178599 | -1.159857 | -0.139527 | -0.230115 | -0.631976 | ... | -0.724172 | -0.421045 | -2.012480 | -2.081784 | -2.734123 | -0.879470 | -2.141218 | 4.598401 | -4.222797 | -2.523024 |

| 2 | 1 | 3 | -4.338502 | -1.756120 | -0.897590 | 1.505972 | -0.925189 | 1.511500 | -2.206561 | 0.132579 | ... | 1.766109 | -2.252858 | -2.919826 | -1.974066 | -0.773881 | 0.244633 | -1.727550 | 1.665467 | 0.562291 | -1.553616 |

| 3 | 1 | 4 | -2.713236 | 0.934866 | 1.987849 | 2.596228 | -0.220666 | -0.480717 | -3.966273 | -0.911226 | ... | 0.856124 | 0.727759 | -0.501579 | 1.077504 | 2.268052 | -3.821422 | 1.629055 | -0.220834 | -1.185091 | -5.462884 |

| 4 | 1 | 5 | -5.782997 | -4.357881 | -3.086559 | 3.796975 | -1.539641 | -2.425617 | -1.020599 | -1.666200 | ... | 2.617215 | -1.231835 | -0.891350 | 0.246981 | 2.489642 | 0.319735 | -2.810366 | 0.585826 | 3.643749 | 0.147147 |

5 rows × 34 columns

Feature preprocessing pipelines#

We can incorporate preprocessing pipelines. For example, when using Lasso, we may want to include polynomial and interaction terms. Here, we create a class that allows us to include, for example, polynomials of order 3 and interactions between all variables.

[14]:

class PolyPlus(BaseEstimator, TransformerMixin):

"""PolynomialFeatures(degree=k) and additional terms x_i^(k+1)."""

def __init__(self, degree=2, interaction_only=False, include_bias=False):

self.degree = degree

self.extra_degree = degree + 1

self.interaction_only = interaction_only

self.include_bias = include_bias

self.poly = PolynomialFeatures(degree=degree, interaction_only=interaction_only, include_bias=include_bias)

def fit(self, X, y=None):

self.poly.fit(X)

self.n_features_in_ = X.shape[1]

return self

def transform(self, X):

X = np.asarray(X)

X_poly = self.poly.transform(X)

X_extra = X ** self.extra_degree

return np.hstack([X_poly, X_extra])

def get_feature_names_out(self, input_features=None):

input_features = np.array(

input_features

if input_features is not None

else [f"x{i}" for i in range(self.n_features_in_)]

)

poly_names = self.poly.get_feature_names_out(input_features)

extra_names = [f"{name}^{self.extra_degree}" for name in input_features]

return np.concatenate([poly_names, extra_names])

For this example we use the non-linear and discontinuous dgp_type="dgp3", with 30 covariates and a true treatment effect theta=0.5.

[15]:

dim_x = 30

theta = 0.5

np.random.seed(123)

data_dgp3 = make_plpr_CP2025(num_id=500, num_t=10, dim_x=dim_x, theta=theta, dgp_type="dgp3")

dml_data_dgp3 = DoubleMLPanelData(data_dgp3, y_col="y", d_cols="d", t_col="time", id_col="id", static_panel=True)

We can apply the polynomial and intercation transformation for specific sets of covariates. For example, for the fd_exact approach, we can apply it to the original \(X_{it}\) and lags \(X_{it-1}\) seperately using ColumnTransformer.

To achieve this, we pass need to pass the corresponding indices for these two sets. DoubleMLPLPR stacks sets \(X_{it}\) and \(X_{it-1}\) column-wise. Given our example data has 30 covariates, this means that the first 30 features in the nuisance estimation correspond to the original \(X_{it}\), and the last 30 correspond to lags \(X_{it-1}\). Therefore we define the indices indices_x and indices_x_tr as below.

[16]:

indices_x = [x for x in range(dim_x)]

indices_x_tr = [x + dim_x for x in indices_x]

preprocessor = ColumnTransformer(

[

(

"poly_x",

PolyPlus(degree=2, include_bias=False, interaction_only=False),

indices_x,

),

(

"poly_x_tr",

PolyPlus(degree=2, include_bias=False, interaction_only=False),

indices_x_tr,

),

],

remainder="passthrough",

)

This preprocessor can be applied for approaches cre_general and cre_normal in the same fashion. In this case the two sets of covariates would be the original \(X_{it}\) and the unit mean \(\bar{X}_i\).

Remark: Note that we set remainder="passthrough" such that all remaining features, not part of indices_x and indices_x_tr, would not be preprocessed but still included in the nuisance estimation. This is particularly important for the cre_normal approach, as \(\bar{D}_i\) is further added to \(X_{it}\) and \(\bar{X}_i\) in the treatment nuisance model.

Finally, we can create the learner using a pipeline and fit the model.

[17]:

ml_lasso = make_pipeline(

preprocessor, StandardScaler(), LassoCV(cv=2, n_jobs=5)

)

ml_lasso

[17]:

Pipeline(steps=[('columntransformer',

ColumnTransformer(remainder='passthrough',

transformers=[('poly_x', PolyPlus(),

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9,

10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16,

17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23,

24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29]),

('poly_x_tr', PolyPlus(),

[30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36,

37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43,

44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50,

51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57,

58, 59])])),

('standardscaler', StandardScaler()),

('lassocv', LassoCV(cv=2, n_jobs=5))])In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook. On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

Pipeline(steps=[('columntransformer',

ColumnTransformer(remainder='passthrough',

transformers=[('poly_x', PolyPlus(),

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9,

10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16,

17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23,

24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29]),

('poly_x_tr', PolyPlus(),

[30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36,

37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43,

44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50,

51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57,

58, 59])])),

('standardscaler', StandardScaler()),

('lassocv', LassoCV(cv=2, n_jobs=5))])ColumnTransformer(remainder='passthrough',

transformers=[('poly_x', PolyPlus(),

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13,

14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24,

25, 26, 27, 28, 29]),

('poly_x_tr', PolyPlus(),

[30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40,

41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51,

52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59])])[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29]

PolyPlus()

[30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59]

PolyPlus()

passthrough

StandardScaler()

LassoCV(cv=2, n_jobs=5)

[18]:

plpr_lasso_fd = DoubleMLPLPR(dml_data_dgp3, clone(ml_lasso), clone(ml_lasso), approach="fd_exact", n_folds=5)

plpr_lasso_fd.fit(store_models=True)

print(plpr_lasso_fd.summary)

coef std err t P>|t| 2.5 % 97.5 %

d_diff 0.517696 0.018044 28.690074 5.074285e-181 0.482329 0.553062

Given that we apply the polynomial and interactions preprossing to two sets of 30 columns each, the number of features is 1050.

[19]:

plpr_lasso_fd.models["ml_m"]["d_diff"][0][0].named_steps["lassocv"].n_features_in_

[19]:

1050

As describes above, for the cre_normal approach adds \(\bar{X}_i\) to the features used in the treatment nuisance estimation.

[20]:

plpr_lasso_cre_normal = DoubleMLPLPR(dml_data_dgp3, clone(ml_lasso), clone(ml_lasso), approach="cre_normal", n_folds=5)

plpr_lasso_cre_normal.fit(store_models=True)

print(plpr_lasso_cre_normal.summary)

plpr_lasso_cre_normal.models["ml_m"]["d"][0][0].named_steps["lassocv"].n_features_in_

coef std err t P>|t| 2.5 % 97.5 %

d 0.560037 0.028292 19.794714 3.306228e-87 0.504585 0.615488

[20]:

1051

For the wg_approx approach, there is only one set of features. We can create a similar learner for this setting.

[21]:

preprocessor_wg = ColumnTransformer(

[

(

"poly_x",

PolyPlus(degree=2, include_bias=False, interaction_only=False),

indices_x,

)

],

remainder="passthrough",

)

ml_lasso_wg = make_pipeline(

preprocessor_wg, StandardScaler(), LassoCV(cv=2, n_jobs=5)

)

[22]:

plpr_lasso_wg = DoubleMLPLPR(dml_data_dgp3, clone(ml_lasso_wg), clone(ml_lasso_wg), approach="wg_approx", n_folds=5)

plpr_lasso_wg.fit(store_models=True)

print(plpr_lasso_wg.summary)

plpr_lasso_wg.models["ml_l"]["d_demean"][0][0].named_steps["lassocv"].n_features_in_

coef std err t P>|t| 2.5 % 97.5 %

d_demean 1.151822 0.014172 81.277037 0.0 1.124047 1.179598

[22]:

525

We can see that for the more complicated data generating process dgp3, the approximation approach performs worse compared to the other approaches.

As another example, below we should how to select a specific covariate subset for preprocessing. This can be useful in case of the data includes dummy covariates, where adding polynomials might not be appropriate.

[23]:

x_cols = dml_data_dgp3.x_cols

x_cols_to_pre = ["x3", "x6", "x22"]

indices_x_pre = [i for i, c in enumerate(x_cols) if c in x_cols_to_pre]

preprocessor_alt = ColumnTransformer(

[

(

"poly_x",

PolyPlus(degree=2, include_bias=False, interaction_only=False),

indices_x_pre,

)

],

remainder="passthrough",

)

ml_lasso_alt = make_pipeline(

preprocessor_alt, StandardScaler(), LassoCV(cv=2, n_jobs=5)

)

plpr_lasso_wg.learner["ml_l"] = ml_lasso_alt

plpr_lasso_wg.learner["ml_m"] = ml_lasso_alt

plpr_lasso_wg.fit(store_models=True)

plpr_lasso_wg.models["ml_l"]["d_demean"][0][0].named_steps["lassocv"].n_features_in_

[23]:

39

[24]:

plpr_lasso_wg.models["ml_l"]["d_demean"][0][0].named_steps['columntransformer']

[24]:

ColumnTransformer(remainder='passthrough',

transformers=[('poly_x', PolyPlus(), [2, 5, 21])])In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook. On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

ColumnTransformer(remainder='passthrough',

transformers=[('poly_x', PolyPlus(), [2, 5, 21])])[2, 5, 21]

PolyPlus()

[0, 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29]

passthrough

We can also look at the resulting features.

Remark: Note, however, that the feature names here refer only to the corresponding x_cols indices, not the column names from the pd.DataFrame because DoubleML uses np.array’s for fitting the model. Therefore the difference to the names from x_cols_to_pre.

[25]:

plpr_lasso_wg.models["ml_l"]["d_demean"][0][0].named_steps['columntransformer'].get_feature_names_out()

[25]:

array(['poly_x__x2', 'poly_x__x5', 'poly_x__x21', 'poly_x__x2^2',

'poly_x__x2 x5', 'poly_x__x2 x21', 'poly_x__x5^2',

'poly_x__x5 x21', 'poly_x__x21^2', 'poly_x__x2^3', 'poly_x__x5^3',

'poly_x__x21^3', 'remainder__x0', 'remainder__x1', 'remainder__x3',

'remainder__x4', 'remainder__x6', 'remainder__x7', 'remainder__x8',

'remainder__x9', 'remainder__x10', 'remainder__x11',

'remainder__x12', 'remainder__x13', 'remainder__x14',

'remainder__x15', 'remainder__x16', 'remainder__x17',

'remainder__x18', 'remainder__x19', 'remainder__x20',

'remainder__x22', 'remainder__x23', 'remainder__x24',

'remainder__x25', 'remainder__x26', 'remainder__x27',

'remainder__x28', 'remainder__x29'], dtype=object)

Hyperparameter tuning#

In this section we will use the tune_ml_models() method to tune hyperparameters using the Optuna package. More details can found in the Python: Hyperparametertuning with Optuna example notebook.

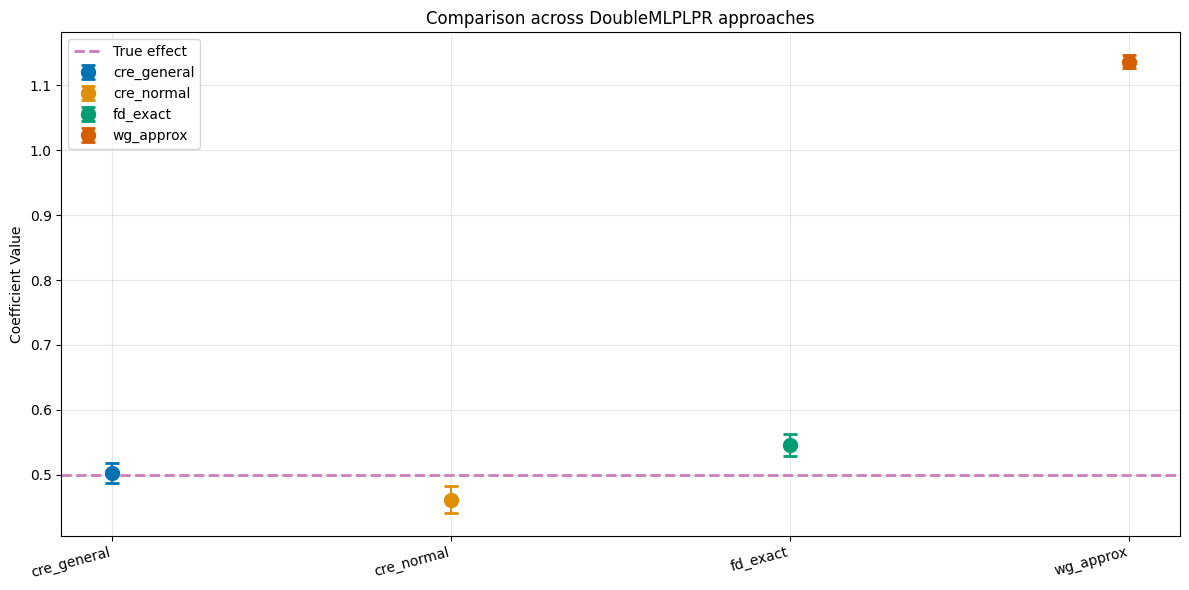

As an example, we use LightGBM regressors and compare the estimates for the different static panel model approaches, when applied to the non-linear and discontinuous dgp3.

[26]:

dim_x = 30

theta = 0.5

np.random.seed(11)

data_tune = make_plpr_CP2025(num_id=4000, num_t=10, dim_x=dim_x, theta=theta, dgp_type="dgp3")

dml_data_tune = DoubleMLPanelData(data_tune, y_col="y", d_cols="d", t_col="time", id_col="id", static_panel=True)

ml_boost = LGBMRegressor(random_state=314, verbose=-1)

[27]:

# parameter space for both ml models

def ml_params(trial):

return {

"n_estimators": 100,

"learning_rate": trial.suggest_float("learning_rate", 0.1, 0.4, log=True),

"max_depth": trial.suggest_int("max_depth", 2, 10),

"min_child_samples": trial.suggest_int("min_child_samples", 1, 5),

"reg_lambda": trial.suggest_float("reg_lambda", 1e-2, 5, log=True),

}

param_space = {

"ml_l": ml_params,

"ml_m": ml_params

}

optuna_settings = {

"n_trials": 100,

"show_progress_bar": True,

"verbosity": optuna.logging.WARNING, # Suppress Optuna logs

}

[28]:

plpr_tune_cre_general = DoubleMLPLPR(dml_data_tune, clone(ml_boost), clone(ml_boost), approach="cre_general", n_folds=5)

plpr_tune_cre_general.tune_ml_models(

ml_param_space=param_space,

optuna_settings=optuna_settings,

)

plpr_tune_cre_general.fit()

plpr_tune_cre_general.summary

[28]:

| coef | std err | t | P>|t| | 2.5 % | 97.5 % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d | 0.495091 | 0.007491 | 66.088483 | 0.0 | 0.480408 | 0.509774 |

0.509102

[29]:

plpr_tune_cre_normal = DoubleMLPLPR(dml_data_tune, clone(ml_boost), clone(ml_boost), approach="cre_normal", n_folds=5)

plpr_tune_cre_normal.tune_ml_models(

ml_param_space=param_space,

optuna_settings=optuna_settings,

)

plpr_tune_cre_normal.fit()

plpr_tune_cre_normal.summary

[29]:

| coef | std err | t | P>|t| | 2.5 % | 97.5 % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d | 0.489759 | 0.010002 | 48.968271 | 0.0 | 0.470156 | 0.509362 |

[30]:

plpr_tune_fd = DoubleMLPLPR(dml_data_tune, clone(ml_boost), clone(ml_boost), approach="fd_exact", n_folds=5)

plpr_tune_fd.tune_ml_models(

ml_param_space=param_space,

optuna_settings=optuna_settings,

)

plpr_tune_fd.fit()

plpr_tune_fd.summary

[30]:

| coef | std err | t | P>|t| | 2.5 % | 97.5 % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d_diff | 0.549295 | 0.008736 | 62.878843 | 0.0 | 0.532174 | 0.566417 |

[31]:

plpr_tune_wg = DoubleMLPLPR(dml_data_tune, clone(ml_boost), clone(ml_boost), approach="wg_approx", n_folds=5)

plpr_tune_wg.tune_ml_models(

ml_param_space=param_space,

optuna_settings=optuna_settings,

)

plpr_tune_wg.fit()

plpr_tune_wg.summary

[31]:

| coef | std err | t | P>|t| | 2.5 % | 97.5 % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d_demean | 1.133962 | 0.005109 | 221.970892 | 0.0 | 1.123949 | 1.143975 |

[32]:

palette = sns.color_palette("colorblind")

ci_cre_general = plpr_tune_cre_general.confint()

ci_cre_normal = plpr_tune_cre_normal.confint()

ci_fd = plpr_tune_fd.confint()

ci_wg = plpr_tune_wg.confint()

comparison_data = {

"Model": ["cre_general", "cre_normal", "fd_exact", "wg_approx"],

"theta": [plpr_tune_cre_general.coef[0], plpr_tune_cre_normal.coef[0], plpr_tune_fd.coef[0], plpr_tune_wg.coef[0]],

"se": [plpr_tune_cre_general.se[0], plpr_tune_cre_normal.se[0], plpr_tune_fd.se[0], plpr_tune_wg.se[0]],

"ci_lower": [ci_cre_general.iloc[0, 0], ci_cre_normal.iloc[0, 0], ci_fd.iloc[0, 0], ci_wg.iloc[0, 0]],

"ci_upper": [ci_cre_general.iloc[0, 1], ci_cre_normal.iloc[0, 1], ci_fd.iloc[0, 1], ci_wg.iloc[0, 1]]

}

df_comparison = pd.DataFrame(comparison_data)

print(f"True treatment effect: {theta}\n")

print(df_comparison.to_string(index=False))

# Create comparison plot

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

for i in range(len(df_comparison)):

plt.errorbar(i, df_comparison.loc[i, "theta"],

yerr=[[df_comparison.loc[i, "theta"] - df_comparison.loc[i, "ci_lower"]],

[df_comparison.loc[i, "ci_upper"] - df_comparison.loc[i, "theta"]]],

fmt='o', capsize=5, capthick=2, ecolor=palette[i], color=palette[i],

label=df_comparison.loc[i, "Model"], markersize=10, zorder=2)

plt.axhline(y=theta, color=palette[4], linestyle='--',

linewidth=2, label="True effect", zorder=1)

plt.title("Comparison across DoubleMLPLPR approaches")

plt.ylabel("Coefficient Value")

plt.xticks(range(4), df_comparison["Model"], rotation=15, ha="right")

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

True treatment effect: 0.5

Model theta se ci_lower ci_upper

cre_general 0.495091 0.007491 0.480408 0.509774

cre_normal 0.489759 0.010002 0.470156 0.509362

fd_exact 0.549295 0.008736 0.532174 0.566417

wg_approx 1.133962 0.005109 1.123949 1.143975

We again see that the wg_approx leads to a biased estimate in the non-linear and discontinuous dgp3 setting. The approaches cre_general, cre_normal, fd_exact, in combination with LightGBM regressors, tuned using the Optuna package, lead to estimate close to the true treatment effect.

This is line with the simulation results in Clarke and Polselli (2025), albeit only for only one dataset in this example.